As I find myself well into the educational phase of my career (that is, passing on what I know to other cooks), I'm discovering that for every moment the world of cooking seemed like an endless expanse of culinary universe, I find that universe shrinking and starting to make more sense each day.

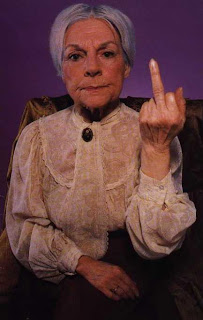

What some sources refer to as the culinary basics, our mothers and grandmothers would call good, common sense. Let's face it; in the realm of chicken and egg scenarios, it's the all-knowing, multi-tasking matron of the hearth who came long before the Certified Master Chef. For all those women who had no choice but to cook for their families when the house was empty of kids or working men, they did so out of necessity and survival, not expression of creativity or ego. Before cookbooks and anything slightly resembling a home-guide for the kitchen were available, determining which pot was best for which dish, when a using a wooden spoon was better than a metal one, when to cover the pot, or leave it open- and when to turn the flame up versus down was trial by fire (pun-intended).

It wasn't until the supposed "masters" like Escoffier and Careme, Brillat-Savarin and other culinary giants came along with their guides and rules for doing it right all the time. Most of these men served careers in the military first. Upon leaving the service, they applied this new-found rigidity and culture of order to the craft of cooking, and in doing so, they turned it into a science. They evaluated things like boiling points of water vs. sugar, they studied the effects of heat and steam on proteins and the differences of various cooking metals (i.e. copper versus aluminum). They wrote the recipes for the basics, and, in short, they codified cooking to remove the guess work and make it a more exact science.

"So", you say, "my grandmother couldn't tell you the exact poaching temperature for a terrine, but I'm certain she has one of the most bad-ass pie crusts you'll ever make!" And, you're right. Ironically, it's the simplest of elements the housewife mastered in cooking that young line cooks and culinary students today can't grasp. I think most cooks think not about putting the final product on a table to actually savor, eat and enjoy, but more about how it will look on the plate. Taste has become secondary. Tsk, tsk, tsk.

More mothers and grandmothers have landed perfect pot roasts and mashed potatoes on kitchen tables they knew tasted good than can most line cooks today, I can tell you. One factor is the incessant distractions for line cooks. They fight boredom, extreme temperatures, long-hours, sleep deprivation, substance abuse, hangovers, ADHD and the insidious Top Chef scenarios which play out in their heads. If only I were competing, I'd show them all! Well, if competing on a cooking show is anything like taking your cooking practical at culinary school where you are judged on technique, creativity, mastery of basics and timing, let's just say that having a camera shoved in your arse won't make it any easier (certainly not on your ego when you're trashed by the judges in front of millions).

Upon graduating from CIA, I landed as a sous chef for my first cooking job. Heading up my first kitchen, I had set a standard for myself: never, EVER, let a dish go out of the kitchen that I wouldn't be proud to serve my parents or my instructors at school. It worked for me. But, line cooks also notoriously have a varying degree of quality acceptance in their heads which could be set very high one day, and very low the next, often depending on the factors mentioned above. To fight that rogue thinking in cooks, I employed a mantra of thinking "ALWAYS". "Always" was the sure-fire way to infiltrate the cob-webby minds of cooks to make sure that whenever considering cutting a corner, taking that shortcut or battling laziness, they would prevail by choosing the one correct route: the right way, always.

And so, this brings us back to why mothers and grandmothers have always had the upper hand on so many aspiring iron chefs, career line-cooks, hot-shot culinary snots and gadget toting food geeks; they learned by trial and error, not from books, a sous chef or even television.

Here then, in no particular order, whether you cook at home, as a hobby or on the chain gang somewhere in the masses of mashed potato houses, are my

Top 10 Things You Can Do to Be a Better Cook:

1. Control Your Heat- Oh, how I've watched a poor dish of veal medallions languishing in a saute pan that isn't hot enough, or a cream sauce on nuclear boil. A stove has knobs; USE THEM!

2. Work Clean- ALWAYS clean after yourself as you go. It is the key to organization mastery. A dirty cutting board is a dirty mind.

3. Be Patient- You can make something fast, or you can make it the right way. Cut corners and you cheat flavor.

4. Taste and Season Often- If you aren't tasting what you're cooking, you are not a real cook, but a robot. Enjoy your life of automated servitude. Or, season and taste your food and build a library of flavors, sensations and a vocabulary that will help you get the most enjoyment out of the culinary arts.

5. Listen- Your food is talking to you. Very often it can tell you that you're doing something wrong, like cooking on too high heat or not enough oil in your pan. Food that snaps, slides, pops and sighs is teaching you about cooking. Listen to it.

6. Smell- Your sense of smell can save you from using fish that is past "safe" or knowing the difference from toasted bread and charcoal. A simple pot of tomato sauce has that "finished" smell when the combination of onion, garlic, tomato and herbs have melded into one harmonious, heady aroma.

7. Use Fresh- If you are ever asking which is the better ingredient(s) to use, the answer will 99.9% of the time be "fresh". Think about it. If taste is priority (and I think we've established it should be), then use fresh products. If you want to cut corners and make a quick stew our soup, use your canned beans, dried herbs and bouillon cubes. If you want to see the difference I'm talking about, try it the other way.

8. Order of Ingredients- There is ALWAYS a right order to put ingredients in a recipe for maximum flavor and/or correctness. And you need to learn why. Sometimes it's scientific, other times it's common sense. A fresh pea takes, what- two minutes to cook? Add it at the beginning of a 45 minute soup, stew or saute and you've killed any flavor, nutritional value or color that poor legume ever had of gifting you.

9. Use Proper Tools and Sharp Knives- You've heard this one a lot. So why do you insist on using tongs for every task, you filthy, dirty little cook, you? There is a big difference between gadgets and proper kitchen tools, particularly spatulas. Same goes for bowls, pots and pans. Stop being lazy. Also, sharp knives are better and safer to work with, always. But, if you insist, go ahead and cut your fingers off. You're giving the rest of us a bad name.

UPDATE: Case in point- this article in the WSJ one day later...

10. Know When to Stop- There is always a time when you should stop; stop beating, stop blending, roasting, adding salt, adding other ingredients or just trying. Read your recipes and listen (ahem) to what they say. This one can't be taught, so you just have to learn it. Or, go ask your mother.